Air pollution indices have never been worse around the world, particularly in Africa. At least nine out of ten people on the continent breathe polluted air, according to environmentalists. Among the causes are dust from unpaved roads, waste combustion and thermal power stations. The consequences range from heart disease to death. In Uganda, for example, 28,000 deaths linked to this phenomenon were recorded in 2017 alone. Faced with this situation, which is partly justified by the lack of data on pollution levels in African countries and often stifles efforts to make the continent's cities more attractive, scientists are scrambling their brains to come up with concrete, local monitoring solutions. One such solution is AirQo, a technological innovation developed by a group of computer scientists and physicists from Kampala.

Clean air for all African cities. This is the leitmotif of the artificial intelligence (AI) software AirQo developed by the eponymous start-up in Uganda. “We provide communities with accurate, hyper-local and current air quality data to drive mitigation actions. In particular, we provide them with evidence of the extent and scale of air pollution across the continent, which they can access in real time via our easy-to-use analysis dashboard or mobile app,” say the Kampala-based researchers. Equipped with sensors and their temerity, they follow the evolution of particles in the soil and swear by “the depollution of Africa”.

The AirQo start-up is made up of some twenty young people supervised by the Bainomugisha academic. They are Joël Ssematimba, head of hardware development and manufacturing, Déo Okure, program manager, Dora Bampangana, project administrator, Martin Babale, head of software engineering, and Richard Sserunjogi, head of data science, who works with scientists Priscilla Adong, Usman Abdul-Ganiy, Wabinyai Fidel Raja, Noble Mutabazi and Daniel Ogenrwot. There are also designers Benjamin Ssempala and Hakim Luyima, who developed the computer interface designed by engineer Paul Zana.

How does it work?

In concrete terms, the team installs monitoring sensors on the roofs of buildings (schools, offices, houses) and even on the back of bodas bodas (the name given to motorcycle cabs in East Africa) to collect data on air quality, particularly in the soil. This is thanks to a digital option that tracks the diffusion of pollutants from their source to their propagation by the wind. This data is then processed and uploaded to the cloud. The experts then analyze the fine particles by category and size.

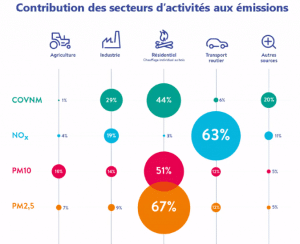

First, the smallest, such as “PM2.5”, which are particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns, equivalent to 0.002 5 millimeters. Then there are the larger particles known as “PM10”, with a larger diameter. It is at this level that AirQo can assess the effects of smoke generated by tobacco, burning candles or oil lamps, as well as cooking stoves and fuel-burning heating appliances (wood, oil, coal). There are also so-called “secondary” fine particles, formed in the air from other pollutants, notably gases such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and ammonia (NH3). A French study confirms that these chemical reactions, sometimes resulting from volcanic eruptions and forest fires, are harmful to the environment.

Pollution by sector of activity ©Meersens Lyon

Once particle concentrations have been determined, the final step for AirQo’s analysts is to translate and insert the information obtained into the mobile application intended for the general public and government officials. The latter can thus download and consult daily information on air quality in the various districts on their smartphones or computers. The aim is to make city dwellers aware of the risks, and at the same time to encourage the authorities to take action to avoid pollution peaks, which have an impact on both human health (eye irritation, runny nose, asthma and above all lung cancer) and biodiversity, according to a report by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). The entire device, which “resists dust and extreme heat”, is powered by solar energy, particularly in the event of a power cut.

The financing

The initiative quickly became an alternative to the energy-hungry, costly ($30,000 per piece imported from the USA) and faulty monitors that municipalities are equipped with. In fact, each sensor in the network deployed by AirQo is worth just $150. The long-term idea is to spread the use of this equipment, enabling governments to save money and maximize resilience measures.

The start-up is backed by a number of partners, including the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), US tech giant Google, whose Google AI Impact Challenge on artificial intelligence AirQo is a winner, the World Bank, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), the US State Department, and of course Makere University, where AirQo was born in 2015.

Factory pollution© VanderWolf /Shutterstock

A breath of fresh air on the horizon…

Although Kampala has a record pollution level (57 μg./m3, seven times higher than international standards, editor’s note), it is not the only target of Ugandan researchers. Other cities, particularly in Central and West Africa, where monitoring equipment is not up to scratch, will follow. These include Cairo in Egypt, home to the industries of several multinational pharmaceutical and agri-food companies, Lagos in Nigeria, which boasts one of the highest population growth rates on the continent (21 million inhabitants), and Nairobi. In the first half of 2023, the Kenyan capital was ranked 5th by the Serbian platform Numbeo in its Top10 polluted African metropolises.

Read also- AFRICA: The continent tops a global ranking on pollution levels

To reverse this trend, the University of Makere, through the expertise of AirQo, is currently collaborating with the UrbanBetter innovation laboratory at the University of Pretoria in South Africa and the Air Quality Monitoring Research Group (AQMRG) at the University of Lagos in Nigeria. The project is part of an inter-regional committee on air purification in the cities of Kampala, Lagos, Bujumbura in Burundi, Yaoundé in Cameroon and Accra in Ghana.

Solutions similar to AirQo exist on other continents. The American space agency NASA, for example, has developed its new “Tempo” instrument. Launched in April 2023 aboard a satellite from Florida, it should enable the detection of fine particles emitted into the atmosphere over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Benoit-Ivan Wansi

You must be logged in to post a comment.