On the occasion of World Water Day, and in partnership with Veolia, a pioneer in the reuse of treated wastewater for drinking water, Afrik 21 is presenting a file on this promising subject. The population explosion in Africa and global climate change are locally exacerbating water stress. In this context, the recycling of treated wastewater becomes an economic and virtuous solution to guarantee access to drinking water. Read our guide on challenges and solutions in 17 questions and answers.

- Water stress: what is it?

- Is Africa affected by drinking water shortages?

- Is global warming making the situation worse?

- What is drinking water, by the way?

- What are the consequences of water scarcity?

- Why does Morocco, like other countries, now rely on “non-conventional” waters?

- Reuse: what is the best way to reuse treated wastewater?

- What are the economic benefits of using treated wastewater as drinking water?

- What are the environmental benefits of using treated wastewater as drinking water?

- Which countries in the world recycle treated wastewater into drinking water?

- Why did Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, choose to make wastewater drinkable?

- Recycling wastewater into drinking water in Windhoek, how does it work?

- What precautions are taken for human health in Windhoek?

- What is the difference between direct or indirect wastewater reuse?

- Can the Windhoek example be replicated? Under what conditions?

- Wastewater reuse, a future solution for Africa?

- Why could Africa become a pioneer in wastewater reuse?

1. Water stress: what is it?

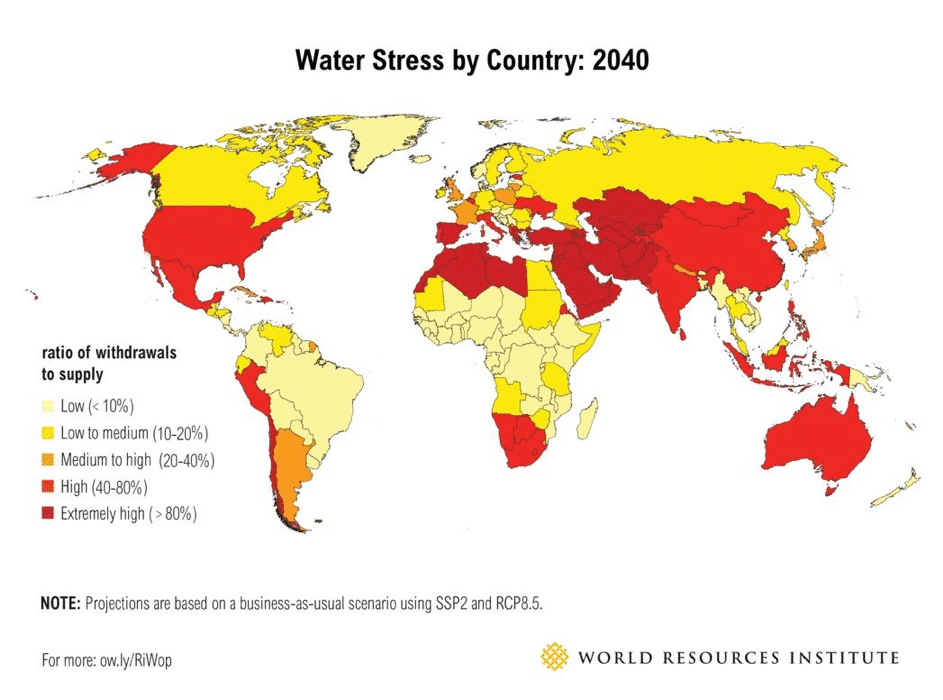

Water stress refers to periods when demand exceeds the amount of drinking water available. The World Health Organization (WHO) refers to water stress when water availability, per year and per capita, is less than 1,700 m3. According to the United Nations, about 3 billion people are expected to face water stress by 2025.

2. Is Africa affected by drinking water shortages?

Africa is affected, as are other continents. The United States, for example, is under chronic water stress, and southern Australia is severely affected by water scarcity. In addition, the UN indicates that the demand for clean water is expected to increase by 40%by 2050 and that at least one in four people will live in a country where the lack of clean water will be chronic or recurrent.

The current demographic explosion in Africa, which will double its population by then, will make water needs explode. The African and Asian continents, which are expected to host 80% of the world’s population by 2030, are the regions likely to experience the most water stress as a result of these severe water challenges, particularly in North Africa and Southern Africa.

Astudypublished by the journal Naturein January 2018 indicates that almost a third of the world’s cities could run out of water in the next 7 years due to climate change, creating usage conflicts with agriculture. Cape Town, South Africa, experienced three long years of drought from 2015 onwards. It had to introduce drastic measures to reduce consumption, and almost found itself in a situation of total shortage. Fortunately, in February 2018, the rain started to fall again…

3. Is global warming making the situation worse?

The link between global warming and the great water cycle (evaporation, saturation, condensation and precipitation) is unanimously recognised by scientists, including in the latest report of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) experts. Locally, the consequences depend on many factors and are not always obvious to predict. However, it is generally known that global warming alters the hydrological cycle. As a result, evaporation is more massive, air absorbs more moisture and precipitation becomes more frequent and intense, causing flooding and droughts here and elsewhere. Studies indicate that the most affected regions in Africa will be North Africa, West Africa and Southern Africa. Multiple adaptation policies will therefore have to be implemented.

4. What is drinking water, by the way?

Drinking water is defined as water that can be consumed without any health risk. To be drinkable, water must have a number of properties: it must be odourless, colourless and tasteless. It must not contain bacteria or viruses, and must not exceed the quantity of authorised chemical substances (heavy metals, nitrates, hydrocarbons, pesticides). Knowing that experts and scientists agree that these chemicals, even when consumed in very small quantities, eventually have health consequences. Thus, as the international authority responsible for public health and water quality, WHO leads global efforts to prevent the transmission of waterborne diseases. For this purpose, it produces international standards on water quality and human health, in the form of guidelines that serve as a basis for the development of rules and standards around the world.

5. What are the consequences of water scarcity?

The lack of drinking water has consequences for all sectors of activity and all social categories. According to the WHO (World Health Organization), by 2016, nearly one billion people worldwide lacked access to a source of safe drinking water and one in three people lacked access to sanitation facilities (toilets or latrines), as did one third of hospitals and clinics. As a result, diarrhoeal diseases (cholera), caused by the consumption of unsafe water and poor hygiene conditions, caused more than one million deaths worldwide in 2018. These diseases are the third leading cause of death in developing countries and the seventh in the world.

Another cause of water scarcity is the difficulty of accessing a natural source, due to the distances generally too long to travel. In addition, the financial cost of obtaining a reliable water source can be a deterrent. As a result, it is usually women and children in Africa who are involved in providing water for the family. They therefore waste most of their time fetching water instead of going to school or work. The struggle for water supply leads to social (with the risk of conflict) and economic (with impacts on agriculture and development) tensions, sometimes accompanied by violence.

6. Why does Morocco, like other countries, now rely on “non-conventional” waters?

Non-conventional water resources are treated wastewater, desalinated brackish water, artificial groundwater recharge and rainwater harvesting. The exploitation of these resources is generally part of the national strategy of States for the mobilisation of water resources in the face of water scarcity.

Since the 1960s, Morocco has adopted seawater desalination for household drinking water consumption.

The Cherifian Kingdom even announced,at the 8th World Water Forum in Brasilia, Brazil, in March 2018, a greater use of non-conventional water resources. Charafat Afilal, the Moroccan Secretary of State for Water, unveiled the country’s new water objectives: “Morocco is a country affected by climate change and cannot be limited solely to rainfall. We must open up to other resources that are not affected by these changes, such as seawater desalination or the reuse of treated wastewater.”

Similarly, for the Emirate of Ajman, Veolia designed and developed 100% reuse of wastewater. The sewerage system collects 100 million litres of effluent from households, businesses and industry every day. Once treated, the water is reused to irrigate tourist complexes, golf courses and fountains, or industrial facilities. A successful example of a circular economy.

For the Emirate of Ajman, Veolia designed and developed 100% reuse of wastewater.

7. ReUse: in what way can treated wastewater be reused?

Morocco, again, aims to ReUse some 325 million m3 of wastewater by 2030, which means moving from a “treatment and discharge” practice to “treatment and reuse” solutions, according to the Moroccan Secretary of State in charge of water. It is a challenging goal.

Morocco is not alone in taking this path. Many experiments are being carried out in Africa. Recycled wastewater is still mainly used in agriculture, for plant irrigation or for watering green spaces. Sometimes also for market gardening, as long as the level of water purification is compatible with this use. Finally, the perfect level of circular economy applied to the small water cycle: the drinking water treatment of wastewater, thanks to complex treatment, is also possible.

8. What are the economic benefits of reusing treated wastewater for drinking water?

In areas facing water scarcity, wastewater recycling into drinking water provides many economic benefits.

Wastewater has the advantage of being precisely where the need for drinking water is felt. This provides a simple and decentralised way to access this resource. Above all, it prevents, in the event of tension on the resource, from fetching water further away and transporting it at high cost because the cost of installing pipelines is significant, with network maintenance and possible leaks, which, all over the world, result in the loss of valuable resources.

Wastewater is also the only resource that grows with needs. In this case, the more people consume, the more they reject, the more they create resources.

All these factors together make it possible to rationalise costs and position the reuse of treated wastewater as drinking water as a solution that is often very advantageous from an economic point of view.

9. What are the environmental benefits of reusing treated wastewater as drinking water?

The reuse of wastewater brings us closer to a circular economy model that is particularly beneficial for environmental protection. This is because the reuse of wastewater avoids the local extraction of scarce freshwater resources.

Most importantly, however, by increasing the number of water treatment cycles, it makes it possible to drastically reduce the pollutant load released into the environment. With fewer pollutants released into the environment, the natural waters that remain, when taken for drinking, are easier and cheaper to treat because they are less polluted. This is called increasing the productivity of raw water.

10. Which countries in the world recycle treated wastewater into drinking water?

The choice of recycling wastewater for drinking water was an innovative option in the 20th century, just as desalination was a few years ago. However, as water demand and water stress increase, this solution, whose costs fell sharply at the beginning of the 21st century, is gradually becoming commonplace. An absolute pioneer in wastewater recycling, the city of Windhoek, Namibia, has been recycling its wastewater into drinking water since… 1968 and a new wastewater recycling plant was commissioned in 2002, which uses advanced technologies provided by Veolia.

The Orange County Water Agency, near Los Angeles, California, USA, has also chosen the wastewater treatment solution to make it drinkable again. Ditto for the city of Goulburn in Australia.

Singapore has also embarked on this path. Today, nearly 30% of the city’s drinking water comes from wastewater treatment plants.

More recently, the South African insurance company, Old Mutual, based in Cape Town, has completely left the city’s drinking water network to provide drinking water for its 9,000 employees through wastewater recycling.

11. Why did Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, choose to make wastewater drinkable?

A wastewater recycling plant in Goreangab, near Windhoek, bordered by the desert.

Located between the Namib and Kalahari deserts, Namibia is considered the driest country in southern Africa. Windhoek, the Namibian capital, with a population of 300,000, is suffering from chronic water stress and is under constant threat of water shortage. Namibia has an average of 250 mm of rainfall per year, which is very low (but remains well above most of the territories bordering the Sahara).

Heat in Namibia causes 83% of this water to evaporate, while only 1% of the resource infiltrates the soil. The local authorities therefore decided, in 1968, to build a wastewater recycling plant in Goreangab, enabling Windhoek to become the first city in the world to produce drinking water directly from municipal wastewater. This has enabled the Namibian capital to provide its population with an additional source of water for more than 20 years.

Following its independence in 1990, Windhoek experienced population growth and the municipality is seeking to upgrade its drinking water supply facilities. In 2001, it signed an operation and maintenance contract with WINGOC (Windhoek Goreangab Operating Company), a consortium composed of Veolia, Berlinwasser International and Wabag, to improve water treatment processes and increase the drinking water production capacity of the Goreangab site.

12. Recycling wastewater into drinking water in Windhoek, how does it work?

Commissioned in 2002, the new drinking water treatment plant in Windhoek now meets 35% of the city and its metropolitan area’s drinking water needs, supplying nearly 400,000 people with a capacity of 21,000 m3 per day.

The water, which comes from the Goreangab dam and the Gammans wastewater treatment plant, is treated according to strict standards. Wingoc implements a multi-barrier treatment. Physical filters, bacterial and chemical treatments ensure that drinking water complies with World Health Organization standards. A sophisticated, yet robust system that takes water through several treatment steps to remove all pollutants and contaminants. These multiple treatments, combined with rigorous biomonitoring programs, guarantee quality drinking water without any health risks.

13. What precautions are taken for human health in Windhoek?

The modernisation of the Windhoek drinking water plant has made it possible to use state-of-the-art technology capable of eliminating any health risks. The “multi-barrier” system reproduces the natural water cycle in several phases: pre-ozonation, coagulation/flocculation, flotation, sand filtration, ozonation, filtration, activated carbon adsorption, ultrafiltration and chlorination. In total, about ten hours are required, from the reception of wastewater from the treatment plant to the outlet of the drinking water station. As a result, this recycled water has led to the installation of new distribution points in the townships as well as additional sanitary facilities. These developments have not only improved the health of the population, but also guaranteed the safety of the most vulnerable people.

14. What is the difference between direct or indirect wastewater reuse?

Windhoek is the oldest project for the direct reuse of treated wastewater for the production of drinking water. This means that the water is then directly consumed, even if three quarters of it is mixed with natural water, which is also treated. The experience gained on this project has demonstrated the feasibility of this type of reuse and the absence of negative effects on public health.

But the indirect reuse of treated wastewater for the production of drinking water is also possible. This involves refilling groundwater used for drinking water production, as is the case in California. Alternatively, surface reservoirs (such as water towers) can also be recharged downstream to ensure the supply of drinking water to the population.

15. Can the Windhoek example be replicated? Under what conditions?

The Windhoek wastewater rehabilitation model deserves to be generalised. The success of this experience is such that the plant now attracts more and more visitors. The President of neighbouring Botswana and several official Botswana delegations, who would consider setting up a similar station in their country, came to discover the Wingoc plant in 2018.

It will also be necessary to ensure that populations are well aware of the upcoming water stress situations, so that they agree to recycle their wastewater in order to better meet their demand for drinking water. In other words, the reuse of treated wastewater can only be considered if drinking water resources are no longer sufficient to supply people with drinking water. And in this case, it often needs to be accompanied by educational efforts, a change in cultural approach, on treated wastewater and sanitation.

16. Wastewater reuse, a solution of the future for Africa?

Despite all the economic and environmental advantages and whatever the water stress situation or the technical and scientific guarantees concerning hygiene and health, projects to reuse treated wastewater for drinking water are sometimes worrying.

It is therefore very important to answer the communities’ questions. Any project to reuse treated wastewater for drinking water requires transparent and honest efforts to explain and raise awarenessby actors and decision makers who have proven their worth and who also share values that inspire trust. All stakeholders must be included in this project.

That being said, no one doubts that wastewater recycling is a solution of the future, including for human consumption. A solution that combines high-tech that closely mimics the natural water cycle and a circular economy concept adapted to the water management of the future. In a United Nations World Water Development Report, presented in March 2017 in Durban, wastewater is referred to as the “new black gold”.

NASA, whose astronauts face extreme living conditions, has also developed a pioneering wastewater recycling project called “Water Recovery System”. Perhaps the famous American space research centre was inspired by Frank Herbert’s (1965) ecological science fiction novel Dune, set on the Arrakis desert planet, where water is so precious that the inhabitants (the Fremen) recycle all the body’s fluids, including perspiration and breathing humidity, in futuristic combinations (Distillates) to be consumed…

As a result, the idea of reusing treated wastewater for drinking water is not new, but could well become the solution of the future for a circular water economy in the 21st century.

17. Why could Africa become a pioneer in wastewater reuse?

The 2017 IPCC report lists 19 major areas in the world that would suffer from abnormally high water stress. Many African countries are affected by this stress: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, South Africa and many parts of West and Southern Africa.

Africa faced with a demographic explosion (with a doubling of the population in 20 years), instead of suffering from climate change and its devastating consequences on water resources, could become, in some aspects, a real laboratory of innovation on water management, where tomorrow’s practices would be invented. Here are two examples that illustrate how countries in the South are innovating in water management.

1. It is in Africa, in Niger to be precise, that the Seen (Niger Water Company) is deploying, with the help of the startup Citytaps and Orange, a revolutionary water meter that allows you to pay for your consumption in prepaid mode via your mobile phone.

In Niger, a revolutionary water meter is implemented, that allows you to pay for your consumption in prepaid mode via your mobile phone.

2. In an interview given in March 2019 to Environnement Magazine, Tristan Mathieu, Executive Director of the Federation of Professional Water Companies, acknowledged that France has not adapted to the new climate change situation in terms of the reuse of treated wastewater and that it is generally lagging behind, especially compared to countries such as Spain, which reuses 14% of its wastewater. The reasons: a past recklessness regarding the availability of the resource and standards so restrictive that they limit authorisations.

Africa could well transform its (water) constraints in the water sector into opportunities, as it is currently doing, in digital and renewable energies, in order to better invent and appropriate new virtuous practices. As it already does, with the reuse of treated wastewater as drinking water in Windhoek, Namibia.

By Jean-Célestin Edjangué and Christoph Haushofer, in partnership with Veolia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.